Assessment and feedback

‘Inclusive assessment and feedback helps to avoid the assumption that certain groups of students have a particular way of learning, when in reality students with disabilities fall along a continuum of learner differences and share similar challenges and difficulties that all students face in higher education.’

Healey et al., 2006

‘There is no one approach to, or definition of, inclusive assessment. Institutions instead are adopting a range of principles under the Inclusive Assessment umbrella, including, but not limited to, using a range of assessment methods, implementing student choice, considering assessment and feedback timing, and developing assessment literacy. Assessment in higher education is neither value-neutral nor culture-free: within its procedures, structures, and systems it codifies cultural, disciplinary and individual norms, values and knowledge hierarchies.’

Hanesworth, 2019

Plymouth’s 7 Steps to Inclusive Assessment offers staff guidance and advice about how to incorporate inclusive assessments into modules. Plymouth offers seven practical steps:

- underpin your assessment with good assessment design principles

- use a variety of assessment methods within your module

- incorporate choice into your assessment

- design inclusive exams

- consider how technology can assist

- prepare, engage, and support students in the assessment process

- monitor, review and share practice

Want to learn more about inclusive assessment?

- If you want to reflect on how inclusive your assessment practices are, or get ideas on how best to enhance you assessments, use Tufts University’s Inclusive Assessment Chart.

- For ideas on assessing students’ knowledge and skills, including during teaching, read 50 Techniques for assessing course-related knowledge and skills

- For helpful suggestions on how to improve clarity of assessment briefs, explore the Assignment Brief Design Website.

- To develop a greater understanding of, and practical tips for, ‘authentic assessments’, read the Authentic Assessment Quick Guide.

- University of Plymouth has created a video library on assessment types and assessment design.

Inclusive feedback

What ‘good’ and ‘useful’ feedback looks like may inevitably vary between students. However, there are some common principles emerged from research, that staff may find helpful.

According to Nicol (2010, ‘From monologue to dialogue: improving written feedback processes in mass higher education‘, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education), good feedback is:

- understandable: expressed in a language that students will understand,

- selective: commenting in reasonable detail on two or three things that the student can do something about,

- specific: pointing to instances in the student’s submission where the feedback applies,

- timely: provided in time to improve the next assignment,

- contextualised: framed with reference to the learning outcomes and/or assessment criteria,

- non‐judgemental: descriptive rather than evaluative, focused on learning goals not just performance goals,

- balanced: pointing out the positive as well as areas in need of improvement,

- forward-looking: suggesting how students might improve subsequent assignment,

- transferable: focused on processes, skills and self‐regulatory processes not just on knowledge content, and

- personal: referring to what is already known about the student and her or his previous work.

Have you ever considered giving students a choice of how they would prefer to receive feedback (e.g., written, audio)? Or asking students to engage in a form of self-assessment or peer assessment?

Encouraging student engagement with feedback

The Educational Development Unit at Imperial has proposed four different techniques to improve student engagement with feedback.

Delaying the release of marks: Teachers can spend large amounts of time writing detailed comments that students spend no time reading. If encourage engagement, try releasing the feedback a few days before releasing the marks. Temporarily withholding marks has been shown to have a positive impact on future student performance (Kuepper-Tetzel and Gardner, 2021, Effects of temporary mark withholding on academic performance.

Posing questions: When marking a piece of work, rather than just telling students what they did wrong and how to improve, pose it as a question rather than an instruction. For example: You suggest that there is a connection between X and Y; what evidence could you have provided for this connection? More importantly ensure that students act on this question (e.g., by providing answers in the next class).

The two-comment rule: You want to help your students focus on the most important parts of the feedback. One method is to provide one statement about what they did well (so that you reinforce what you want them to repeat) and one comment on where they can improve in the future. Providing direct feedback about where they could improve their work will help them gain marks in future assessments of a similar type.

Start/stop/continue: An alternative way of thinking about feedback is to focus your comments on: i) what the student should start doing, 2) what the student should stop doing, and 3) what the student should continue doing.

Want to learn more about feedback strategies?

- Read the HEA feedback toolkit. The resource was created as a reference guide for lecturers wishing to improve their feedback strategies.

- To learn more about practical strategies to implement each of the seven feedback principles, download the practical recommendations for making feedback more effective, from Imperial College London.

- To help students actively engage with feedback, download the “students guide to feedback”, a resource written by Anna Maria Jones, Teaching Fellow at Imperial College London

- Download the Feedback Evaluation Checklist, written by the University of Reading to self-review your feedback practices.

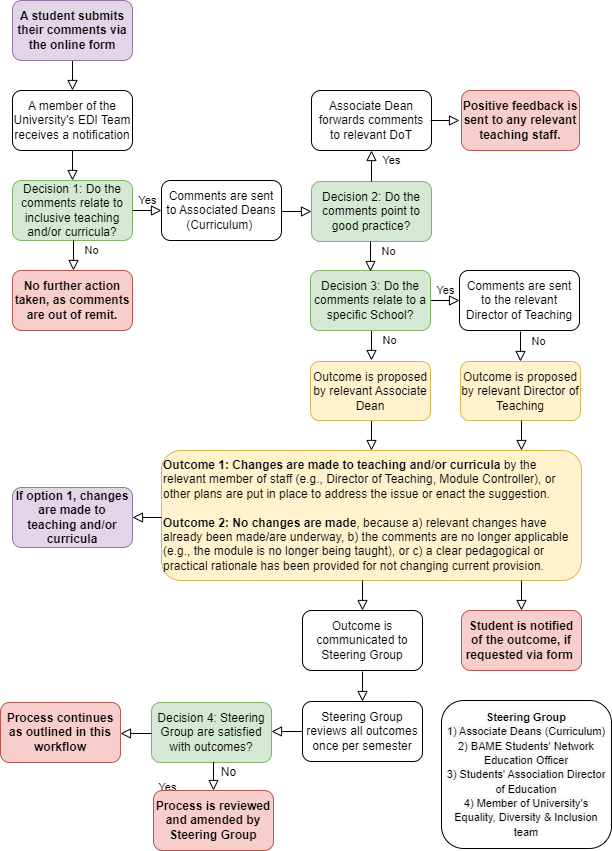

Inclusive curriculum feedback workflow